Shifting Paradigms in Leadership: Implications of the Anesthesiology Workforce’s Bimodal Age Distribution

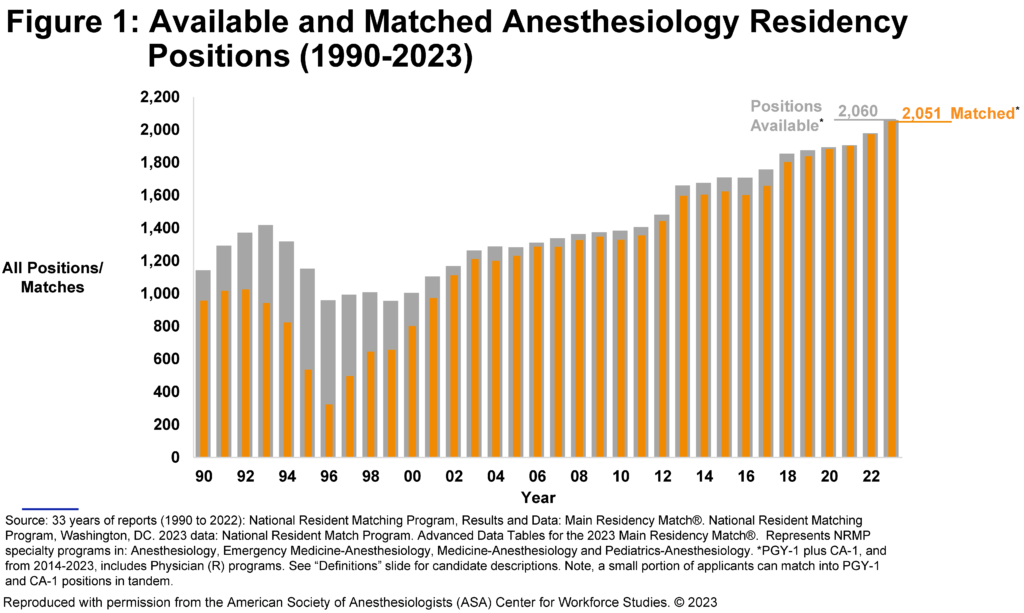

The early 1990s saw a shift in national healthcare policy with a focus on primary care and capitated payment models, igniting apprehension about the future of specialized medicine, elective surgery, and anesthesiology. These and other concerns were reflected in the 622 unfilled anesthesiology residency positions in the 1996 Match, and Match trends did not stabilize until the early 2000s (Figure 1). Despite initial concerns, demand for anesthesiologists escalated, resulting in workforce shortfalls that continue to shape academic anesthesiology.

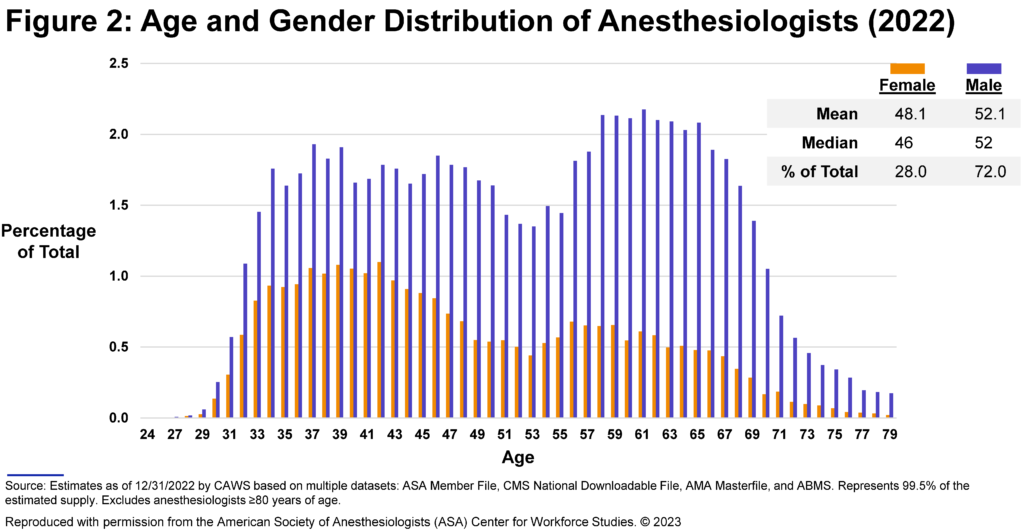

A significant consequence of these past fluctuations is today's bimodal age distribution within the anesthesiology workforce (Figure 2). As of 2022, data from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Center for Workforce Studies unveils two peaks: one cluster of early-career individuals and another nearing retirement, yet a noticeable scarcity of mid-career professionals, with the age distribution's trough occurring at age 53.

This age maldistribution has most obviously complicated recruitment for chairperson roles but also poses nuanced implications for leadership in academic medicine. The lack of anesthesiologists in their late 40s and 50s has created opportunities for early-career individuals to advance more rapidly in their careers. As a result, there has been a discernible trend, at least subjectively, toward younger individuals assuming major leadership roles. While this shift certainly presents important opportunities, it also carries distinct implications and gives rise to specific challenges that need to be addressed (Table 1).

| Implication | Challenges to Address |

| Mid-career faculty recruitment | A competitive landscape leads to varied access to mid-career faculty across departments |

| Mentorship and sponsorship | The need for alternative mentorship models due to young leaders' potentially limited access to mid-career mentors |

| Work-life balance | Balancing personal pressures and major service roles for younger leaders, who face distinct life phase challenges |

| Burnout | The potential for burnout from early leadership roles due to various contributing factors |

| Scholarship | Reduced time for personal and programmatic academic development due to early leadership roles |

| Succession Planning | The need for proactive planning to ensure leadership and operational continuity in the absence of mid-career faculty |

While this bimodal age distribution has certainly impacted leadership transitions in academic anesthesiology, its implications are more far-reaching. This unique age distribution influences not only who is leading, but also how leaders carry out their roles amidst diverse age groups. Furthermore, it impacts the dynamics, cooperation, and performance of the broader workforce.

In an unprecedented demographic shift, today's workforce comprises five distinct generations: Traditionalists, Baby Boomers, Generation Xers, Millennials, and Generation Zers. Given this reality, it is essential to understand the intergenerational differences in work attitudes, behaviors, and motivation to shape future leaders effectively.

Generational research is currently predominated by two theoretical camps. The generational cohort theory [1] posits that each generation is molded by the unique historical, political, and technological changes they experience during their formative years. These shared experiences, in turn, influence their collective work attitudes and behaviors. Indeed, small differences have been demonstrated between generations [2-4]. However, the empirical evidence supporting significant intergenerational divergence in workplace values is somewhat sparse [5, 6], lending credibility to the alternative camp: the lifestyle development perspective [7, 8]. This theory proposes that individual beliefs and attitudes evolve more due to personal life events—such as early childhood dynamics, career changes, and relationship experiences—than to generational factors.

Amid rapid workplace evolution and emerging technologies, organizations must leverage the rich diversity of knowledge and experience found within their multi-generational workforces. However, they must also exercise caution to avoid categorizing workers purely by birth year, as this risks engendering generational stereotypes or, even worse, fostering workplace discrimination. Given the scant evidence of marked generational differences, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine undertook a rigorous review of the literature, resulting in key recommendations for managing a multigenerational workplace [9]. These guidelines echo findings in organizational psychology and leadership literature [10-14] that can inform strategies for building effective intergenerational leaders:

- Inclusive leadership representation, encompassing a broad array of experiences, cultures, educational backgrounds, and personal attributes [9].

- Fostering open knowledge exchange and diverse perspectives, empowering leaders of all generations to provide constructive criticism and engage in decision-making [9, 13].

- Acknowledging and discussing varying expectations of leadership across individuals, not generational cohorts. These insights should inform leadership development programs, fostering a range of leadership values, behaviors, and skills [10].

- Recognizing that motivation is more individual-centric than cohort-centric. Development plans that account for career progression preferences, networking and collaboration needs, and task interests are more effective [12].

- Providing formal leadership development opportunities throughout an individual's career, supporting continuous skill acquisition [9, 11].

- Debunking myths and stereotypes by highlighting generational commonalities, promoting diverse communication styles and fostering collaborative relationships within mixed-generation teams [13].

- Offering engaging and varied work activities, increasingly valued across all generations [14].

- Supporting leaders through their lifecycle by providing job flexibility, autonomy, and promoting work-life balance, thereby encouraging career progression at all stages [9, 11, 14].

Recognizing the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the bimodal age distribution in the anesthesiology workforce, and the broader generational mix in the workplace, is not just a matter of academic interest but a practical necessity. Acknowledging and confronting the challenges unique to younger individuals serving in major leadership capacities is one such necessity. Creating an environment that fosters growth, mentorship, and professional development for all, while avoiding the pitfalls of generational stereotyping and discrimination, is an important step. The future of academic anesthesiology will be shaped not just by our collective technical and scientific expertise, but also by our ability to learn from each other across generational divides, harnessing our diverse experiences, perspectives, and skills to build a stronger, more adaptable, and more inclusive profession. Our ability to meet these challenges today—both for our leaders and the broader workforce—will determine the health of our discipline for generations to come.

References

- Mannheim K. The problem of generations. In P. Kecskemeti (Ed.), Karl Mannheim: Essays (pp. 276–322). 1952; New York: Routledge.

- Twenge JM, Campbell SM. Generational differences in psychological traits and their impact on the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2008; 23: 862-877.

- Myers, K. K., & Sadaghiani, K. Millennials in the workplace: A communication perspective on Millennials’ organizational relationships and performance. Journal of Business Psychology. 2010; 25: 225-238.

- Sessa VI, Kabacoff RI, Deal J, Brown H. Generational differences in leader values and leadership behaviors. The Psychologist-Manager Journal. 2007; 10(1): 47-74.

- Costanza D, Finkelstein L. Generationally Based Differences in the Workplace: Is There a There There? Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2015; 8(3): 308-323. doi:10.1017/iop.2015.15

- Kelleberg AL, Mardsen PV. Work Values in the United States: Age, Period and Generational Difference. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2019; 682(1): 43-59. doi: 1177/0002716218822291

- Riley MW. Aging and cohort succession: Interpretations and misinterpretations. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1973; 37(1): 35–49.

- Elder GH, Jr. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998; 69: 1–12.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Are Generational Categories Meaningful Distinctions for Workforce Management?. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2020. https://doi.org/10.17226/25796.

- Cennamo L, Gardner D. Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person-organization values fit. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2008; 23: 891-906.

- Rudolph CW, Zacher H. The kids are alright: taking a stock of generational differences at work. Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP). 2018. https://www.siop.org/Research-Publications/Items-of-Interest/ArtMID/19366/ArticleID/1431/The-Kids-Are-Alright-Taking-Stock-of-Generational-Differences-at-Work. Accessed May 28, 2023.

- Wong M, Gardiner E, Lang W, Coulon L. Generational differences in personality and motivation: Do they exist and what are the implications for the workforce? Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2008; 23(8): 878-890. DOI: 10.1108/02683940810904376.

- Lester SW, Standifer RL, Schultz NJ, Windsor JM. Actual versus perceived generational differences at work: An empirical examination. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2012; 19(3): 341-354. DOI: 10.1177/1548051812442747

- Kalleberg AL, Marsden PV. Work Values in the United States: Age, Period, and Generational Differences. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2019; 682(1), 43–59. DOI: 10.1177/0002716218822291