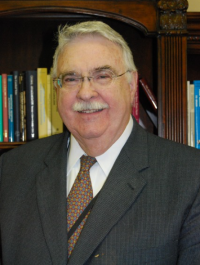

Richard J. Traystman, PhD / 1942-2017

On October 19, 2017, our specialty lost a research giant, Dr. Richard “Dick” J. Traystman. Dick was an important contributor to the foundation of knowledge for Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine and served as a mentor and friend to many in our specialty. In fact, during his career he served as a mentor to more than 100 individuals, many of whom have gone on to become leaders throughout medicine and science—in the U.S. and around the world. These mentees have ultimately developed into academic leaders, including department chairs and deans, as well as leaders in pharmaceutical companies. It is clear to all of us in Anesthesiology that Dick led a life of influence and his mentorship has helped enhance academic anesthesia and leaves a legacy that continues to grow through the many people he encouraged to do research.

On October 19, 2017, our specialty lost a research giant, Dr. Richard “Dick” J. Traystman. Dick was an important contributor to the foundation of knowledge for Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine and served as a mentor and friend to many in our specialty. In fact, during his career he served as a mentor to more than 100 individuals, many of whom have gone on to become leaders throughout medicine and science—in the U.S. and around the world. These mentees have ultimately developed into academic leaders, including department chairs and deans, as well as leaders in pharmaceutical companies. It is clear to all of us in Anesthesiology that Dick led a life of influence and his mentorship has helped enhance academic anesthesia and leaves a legacy that continues to grow through the many people he encouraged to do research.

At the time of his death, his CV included more than 475 publications. His work in the areas of collateral ventilation, control of cerebral circulation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and cerebral ischemia have all been of critical importance to informing anesthesiologists and intensivists in the care of our patients. During his career Dick received numerous honors and prizes, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Excellence in Research Award, the inaugural Laerdal Memorial Lectureship from the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the American Heart Association’s Distinguished Scientist Award and the American Stroke Association’s Willis Lecturer. In 2017, Dick received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Society for Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism.

Dick was passionate about his science and his role as a mentor. He never cared if his mentee was a member of his own department or laboratory. He only cared (insisted) that each of his mentees approach their science and their life with an open mind and with complete commitment to seeking the truth. He pushed all around him to address questions that could be easily translated to improve human health. From the very beginning Dick insisted that we work as a team. In fact, nobody in his department had their own laboratory, as Dick believed that sharing of all resources would assure strong collaboration, excellent communication, and that we would enjoy the strengths of each member of the team. Dick’s approach to “Team Science” assured the success of the group through an incredible personal dedication to each member of that team. Dick’s team science vision pioneered the integration of PhD and MD researchers in anesthesiology departments, leading to productive research and opening the mind to all regarding the importance of cross-discipline discussion to address translational research questions.

My first encounter with Dick was more than 40 years ago; I was a student at Michigan and he was the Vice Chair of Research in the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at Hopkins. On the day that I met him I will never forget the passionate debate that he was having with my Michigan mentor (Dr. Louis D’Alecy) regarding autonomic control of the cerebral circulation during a FASEB meeting; they were screaming at one-another across the room! From that point on I knew that Dick was an incredibly gifted scientist and that he was someone who I wanted to work with in my future. That wish came true 35 years ago and since that time Dick served as my primary research mentor, friend, and colleague. The bond that Dick and I shared for so many years benefited me in my approach to mentorship with my own mentees as well as my personal relationships.

Dick’s accomplishments in science were due to his incredible intelligence, work-ethic (he was reviewing and editing manuscripts and grants until the very end), his welcoming attitude to new ideas from junior members of his team and attention to detail. The first manuscript that I wrote with him went through 21 revisions before he let me submit it to the journal for consideration. His written feedback to me was often filled with aggressive (sometimes foul) language in order to get his point across and get us used to dealing with difficult reviewers. As my co-author Paco—and all who ever wrote a paper or grant with Dick—can confirm, Dick was consistently the most difficult reviewer.

Although Dick’s professional life was spent in Baltimore (Hopkins), Winston Salem (Bowman Gray), Portland (OHSU) and Denver (University of Colorado), he was always a New Yorker (where he was born) at heart. He loved watching the performing arts (particularly Opera and Symphony). Even after moving away from the East Coast, Dick and his wife Suzann continued to enjoy the New York style performing arts, streamed live from the Met. Although he played semi-professional football in his youth his preferred spectator sport was baseball (yes, he was a Yankee fan).

Dick leaves behind his loving wife Suzann Lupton of Denver, Colorado. In lieu of flowers, his wish was for donations to be made in his name to the American Stroke Association.