The Leaky Pipeline: How Are We Addressing This Problem?by Odmara L. Barreto Chang, MD, PhD and Niti Pawar, BA

Despite the strides anesthesia has made to improve racial equity and strengthen the pipeline, diversity continues to be challenging.1,2 In 2020, <15% of anesthesia residents were URiM.3,4 A study from 2023 illustrated that Black and Latinx anesthesiologists lacked representation at each level of the pipeline: medical students (8.1%, 6.8%), anesthesia residents (5.0%, 4.6%), assistant professors (5.1%, 2.9%), associate professors (4.1%, 3.3%), and professors (2.4%, 1.5%).5 It is critical, now more than ever, to address barriers with increased support and intentional action starting from K-12 school, to significantly improve physician representation upstream. Concerns regarding the leaky pipeline have come to light in the context of four decades of stagnating matriculation of URiM medical students.6 Not only are URiM groups significantly less likely to enroll to residency,7 but also, 18.7% of anesthesia applicants reported experiencing discrimination due to gender, race and/or ethnicity.8 The lack of URiM physicians is consistent beyond anesthesia; internal medicine and surgery residencies similarly have <15% URiM residents.9,10

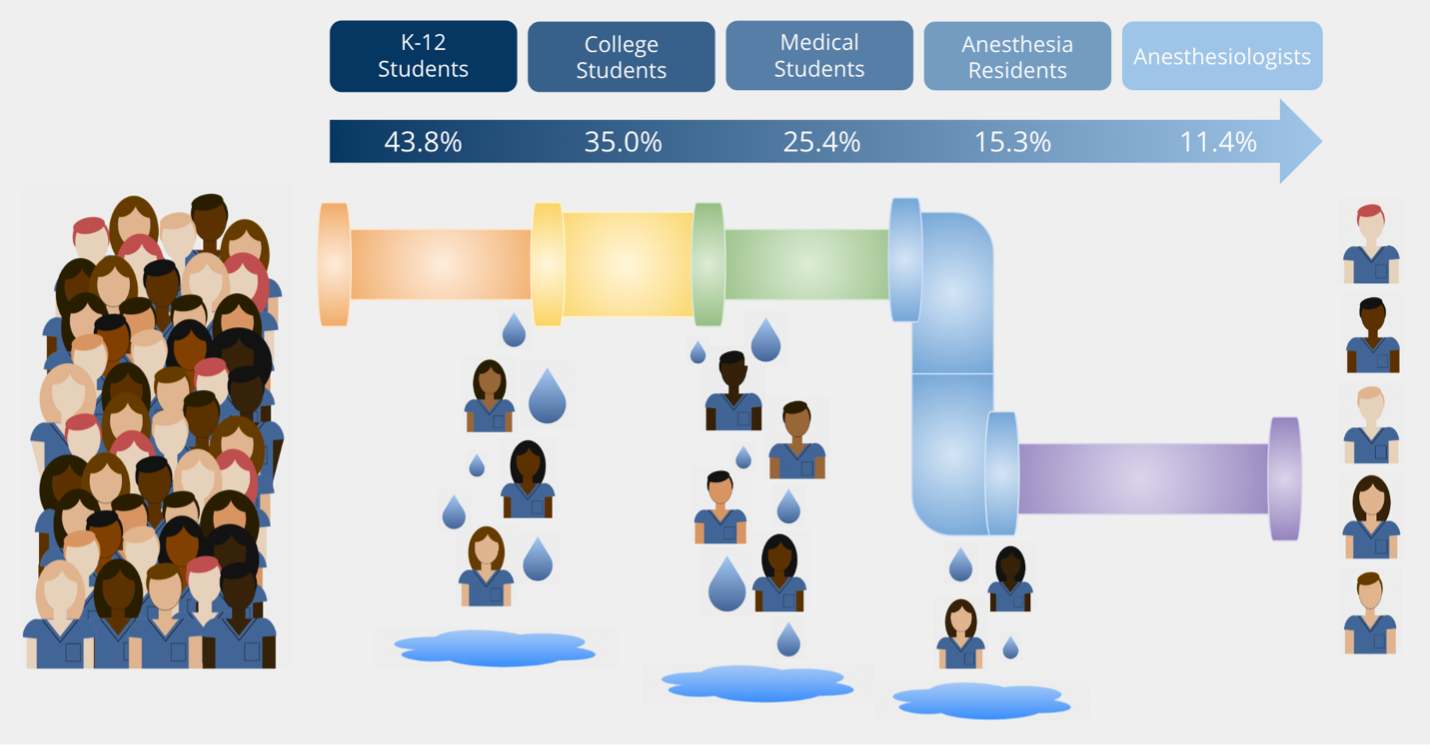

Figure 1. Image illustrates the percentage of underrepresented in medicine (URiM) trainees at each stage of education and career in the United States.11-16 URiM trainees include those identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish Origin and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Pipeline into Anesthesia To improve diversity in medicine and anesthesia, the pipeline into medical school must be improved in parallel efforts––starting at a young age and continuing each step of the way. Many programs host educational opportunities in STEM and health careers to expose K-12 students to science and medicine. This is valuable to elucidate physicians’ journeys and challenges and provide mentorship navigating the arduous road and building confidence that they too, can become doctors. Many also aid with college, medical school, and residency applications including test preparation, career counseling, mock interviews, essay editing, and more. Lastly, grants and scholarships for research, rotations, and schooling are invaluable to helping reduce the barrier of cost that many URiM and first-generation students face. Investing in these pipeline programs will pay forward in multifold to increase the percentage of URiM students graduating from college, medical school, and residency, as well as entering leadership, academia, and becoming physician-scientists, ultimately creating a more diverse workforce more accurately mirroring our patient populations. Limitations Despite the positive impacts of these diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and pipeline efforts, it is essential to address limitations. For instance, the effectiveness of upstream initiatives is limited by the low number of URiM students downstream. Those who make it through are then burdened with the “minority tax”–– the expectation that URiM physicians should take on the responsibilities of diversity initiatives, which can hinder training, rest, self-study, and other professional advancement.6 A study evaluating “minority tax” showed that increasing URiM residents helped mitigate “minority tax” by redistributing the responsibilities among a larger URiM pool. Additional strategies should encourage engagement of the whole anesthesia community, including non-URiM participants that can help promote these efforts. What Should We Do? Departmental strategies, framework, and recommendations are eloquently summarized by Nwokolo et al., including early outreach programs, de-emphasizing entrance metrics (i.e., USMLE scores), bias training for selection committees, targeted recruitment/cluster hiring, fair and transparent opportunities, as well as promotion transparency.17 There is no single solution to this problem, rather, it is crucial to have active participation by the whole medical community to promote early exposure, mentoring, and retention to fix the “leaky pipeline.” It is known that patients who receive care from providers from the same cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, speak the same languages, look similar, and can relate to them have better patient and provider outcomes.17,18 Working on building systems for a diverse workforce has also been associated with improved healthcare access for underserved populations and more expansive research.19 Investing in the anesthesia pipeline will pay itself back many times over; a future generation with a truly diverse physician workforce would reap the many benefits this would bring to patient and physician well-being. A summary of state and national DEI and pipeline initiatives in the U.S. will be available on AUA’s website in early 2024. References:

Authors |